The journalists of Washington, D.C., know politics well. They watch it play out every day. They navigate it among themselves every day, too. It’s a rough town that way. Make a wrong step, and you could find yourself sitting alone during lunchtime in the filing center.

“‘You might ignore politics, but politics will not ignore you.’ —Pericles”

As a person, I hate it. As a photojournalist, I love to hate it.

It’s the ultimate spectator sport. In politics, it’s scripted, of course, like the World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) — sorry, should have given a spoiler alert — but each person works from their own script. One might expect a Tombstone Piledriver only to walk into a Canadian Destroyer. Similar yet distinct. Miscommunications happen. Agendas differ. People get hurt.

Like I said, it’s a rough town and the journalists set the tone.

Naturally, the writing side of things has controlled photojournalism since it’s inception. It makes sense, words were invented way before cameras (although communicating visually trumps them both).

I’ve stopped believing word-based journalists are apolitical. Sadly, based on my Facebook “friends,” I suspect many camera-based ones aren’t either. Sharing political memes and opinions publicly is a dumb move for journalists. It undercuts your career’s work, undermines your profession, and makes you less effective.

Everyone has opinions, and you’re entitled to them. They’re embedded in your work. Don’t suppress them, just avoid letting them distort your reporting. That’s where a camera helps. It’s still possible to lie when you push that button, but it’s a lot harder than when you have twenty-six buttons to play with.

I’ve got no inside information on how the Pulitzer judging for spot news went this year, but we can be certain it came down to the images made by the four photojournalists working in the buffer zone when candidate Trump was shot in Butler, last year.

The Pulitzer committee typically shares commentary, which I haven’t reviewed.

The four journalists were Evan Vucci of The Associated Press, Anna Moneymaker of Getty Images, Jabin Botsford of The Washington Post, and Doug Mills of The New York Times. They all made extraordinary images that day. They are to be commended. I know some of them slightly and have worked next to Doug, who won the Pulitzer, a few times. Each deserved the award.

That said, here’s my quick analysis. Like everything else in this piece, it’s just my opinion.

Evan had the image that will eventually appear on a postage stamp. No small feat, which likely doomed him in the Pulitzer race. Jabin had his head on a swivel. He saw more than anyone else that day. Also no small feat. Anna did something extraordinary when she found a truly private, and I think, revealing moment, in an absolutely public event. None of the others managed to do that. Doug must live right, because that bullet-time image is also unbelievable.

If I was the sole judge, I would have given them all the award. The public record they gave us on that day is deserving of such a thing. If I had to choose one, I’d go with Anna’s. Given time, that image might be the one that keeps historians fascinated for centuries to come. Doug has the complete package and the bullet image undoubtedly put his entry over the top. That said, it’s the most “picture of record” image from the day and that’s what word people love. So in some ways it’s an example of the status quo once again (although picture people are involved in the judging, their recommendations are forwarded to the publishers who make the final call on who wins the prize). Which is something I believe we need to move away from.

Photojournalists can learn to write. Trust me, it’s not that hard. Word people can not learn to make great images. They don’t have it in them, for reasons that deserve a separate essay.

Like I said above, all the them deserved the Pulitzer. More importantly, I don’t know how any of them vote. That’s rare among journalists today. We just need to make our pictures and let them do most of the talking — once thought of as a slight, it’s now an advantage, one of the few we enjoy as lens-based workers.

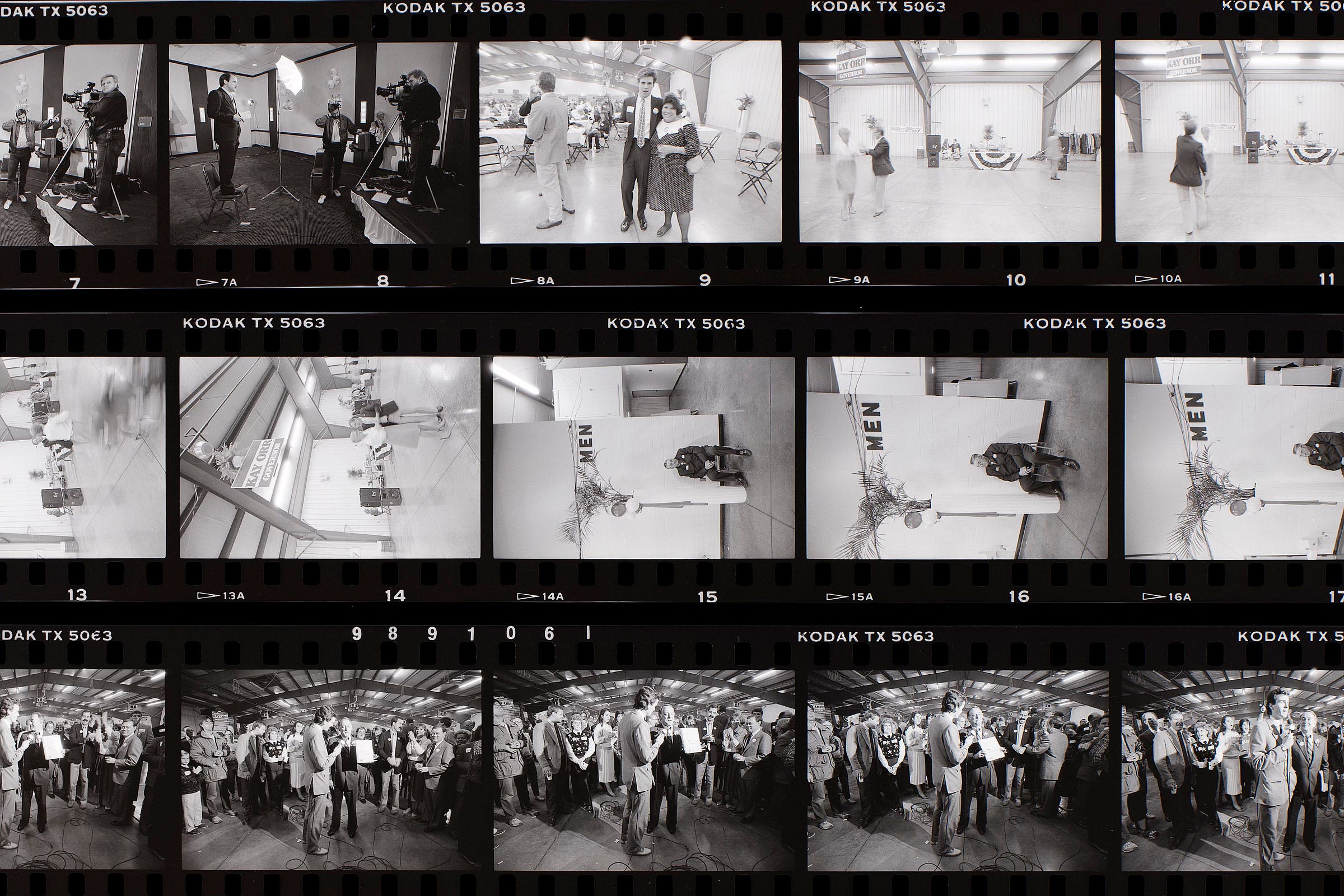

Traditionally, there have been three kinds of photojournalists: wire, newspaper, and magazine. They were classified by their publications’ needs and the images they produced. To understand this, imagine it’s 1983, and you’re traveling with the Reagan campaign.

If you’re an Associated Press photographer, you’re working mainly in black and white, though you may do the occasional color project. You’re using Tri-X and don’t hesitate to push it, as your work will be reproduced on rough newspaper stock. A second AP photographer grabs your film and takes it back to the bureau to process and get it on the wire. Speed is essential. You serve papers worldwide, across time zones, meaning someone’s always on deadline. The image that arrives in their office first will usually win, often against your main competitor and best friend, the United Press International (UPI) photographer. Winning that race is your main goal. The moment’s quality matters, but speed still kills.

Most newspaper photographers are regional. There are a couple of national papers, traveling with the campaign. Most rely on The AP to process and transmit their daily images. Local photographers return to their offices and follow their standard workflow. They and the national papers cover the event to offer readers something different — and sometimes better — than wire coverage, while adding their own local perspective. They’re on normal deadlines, starting in the late afternoon and running into the night, based on their circulation. They might need a color image for page one, too. Speed isn’t the main issue anymore. Their images need to last twenty-four to thirty-six hours.

In some ways, magazine photographers have the easiest job. They have one weekly deadline. They ship their film every night with a courier, who comes to their hotel at the end of the day, so they’re not under a time crunch. If an event has bad light or poor access, they can attend for protection purposes without worrying about making a real picture. They have a week to make the best possible campaign image — the best light, the best moment, no time crunch, maybe special access — all work in their favor. Their work is printed on higher-quality paper, and, at this moment in history, they’re shooting color transparency film. These factors raise the stakes, but their real challenge is making an image that lasts on the newsstand at least a full week. If they fail, freelance agency photographers, whose agents are licensing to the same magazines, or even a great wire image from the week, can beat them.

So that’s why they got paid the big bucks.

They also needed a more editorial than newsy approach. They had to make images that implied a campaign’s or candidate’s inner workings. Thus, often, their images were more graphic, ambiguous, or even pretty — less about a specific “news” moment and more artsy. They’re still true photojournalism, but with a reflective quality.

That’s how photojournalism worked back in the heyday, for lack of a better phrase. It evolved from the flash-for-cash, Speed Graphic days on the White House lawn — don’t show FDR in his wheelchair — to the standards of LIFE’s Bill Eppridge, RFK’s friend and fly on the wall until the very end, and Contact Press Images’ David Burnett shooting Kodachrome, shipping Wednesday night, so he could kill someone else’s double-truck shot on E-6 by Friday night.

And photojournalism continues to evolve today, blending old roles with new demands.

Today photographers are a cross between what wire and newspaper photographers used to be back in the day. They are always on deadline — the online world demands it. Both technical quality and the quality of the moment are paramount. The AP and Getty Images are wires, but The New York Times is a news service, and The Washington Post syndicates its pictures, so they all fill similar needs.

On top of that — let’s ignore the video aspect for now — they occasionally need to make a magazine-style image, too.

That’s a lot. Something has to give: the magazine-style images, gave.

You can use the images from Butler as a benchmark, but don’t use them as an excuse for not capturing the everyday revealing images.

Extraordinary situations often — and in this case with these photographers — lead to extraordinary images. But the trick is to make extraordinary images of the mundane.

These four — Doug and Evan especially — have earned a seat at the high table. But I haven’t seen images from them, or any photographers, showing the biggest story in our lifetime. Let’s face it. it’s no longer biased or sensitive to say Joe Biden was mentally unfit to serve, now that it’s too late and (as far as I know) the pictures don’t exist.

I could see it from Montana. I guarantee those working the White House beat could see it too. I know access was miserable, but they needed to make those pictures.

The White House News Photographers’ Association was founded in 1921, during a time when photographers stood outside the White House gates, hoping to capture policymakers coming and going. It was founded to ensure photojournalists (stills and video) have access to record events firsthand and to fight restrictive policies.

I’m picking on them because they’re the best group that collectively represents the photojournalists working inside of the Beltway today.

The WHNPA didn’t complain about the Biden administration severely limiting access to photojournalists, unlike their response to other administrations.

They did complain when the Obama administration’s heavy use of handouts threatened their role. This followed The New York Times using one of Pete Souza’s images, then Obama’s photographer, on the front page. That makes sense, as it could put them out of business, but I blame The New York Times for letting that genie out of the bottle.

They also complained when The Associated Press lost its privileged access to the Oval Office for clashing with Trump. Stupid word-based political decisions, cloaked in journalistic ideals, made that happen.

Despite all of this, the WHNPA celebrated their awards with President Biden, who (we are told) hired the people limiting their access and actively working against them.

They should have been the administration’s biggest critics. Instead, they largely followed the scribblers lead (as is our habit).

These are the kind of actions that tell me how you vote. That’s not our job — the White House Correspondents’ Association already has that handled. Don’t tie your wagon to that sinking ship.

People, potential customers, currently hate the legacy press. They’ve replaced them with their own media. As photojournalism continues to evolve, it would be helpful if we worked together to preserve our own legacy.