Rocks, three of them, flying through the air heading straight towards the tightly packed crowd of funeral goers. That makes sense, I sarcastically thought. Who throws rocks at a funeral? I mean, at the very least it’s rude and what good would it do anyway?

Somebody’s getting an ass whooping.

That’s when the first rock exploded.

Nothing makes sense here.

Where’d those other two “rocks” land and were there only three of them?

I have no idea. I might be standing right on top of one.

I should have been paying more attention. I had foolishly thought that any chance of violence had ended when the funeral procession had crossed onto the cemetery grounds. Like it was sacred ground or something. What did I know? I was a kid and had been in Northern Ireland for less than 24 hours. Most of the social niceties of this conflict had worn away decades, if not centuries before I got here.

Hoping that I picked the side opposite of where those other two exploding rocks had landed, I took cover behind a tombstone. I tried to fight the tunnel vision and the panic that was spiraling in on me. I consciously worked to widen my field of view and started looking for pictures.

That’s why I’m here. Really, the only reason. Which is to make pictures that, and this is the tricky part, have an impact on those who see them.

There are plenty of other photographers here, but unlike me, most of them are working in the traditional journalistic manner, which is to document things as they happen. The five W’s and all. There are a couple of British military helicopters orbiting overhead filming everything as well. Documentation isn’t the issue.

My goal is to make images that resonate with the viewer and that’s the tricky part.

This is my normal approach, regardless of the subject matter. We could be talking sports photos, politics, the street, or hard news, anything, but regardless of the subject, the idea is to always be working to make pictures that transcend the moment. Lasting images.

Which, when phrased like that, is a terribly arrogant approach to take. Admittedly, I’m guilty as charged, though I’m not alone in this mindset.

You see, there are two basic schools of photojournalism.

The first is a traditional, wire service approach. The aforementioned five W’s. These are the images that you see, or once saw, in your local newspaper. They are focused on the facts and because of the low quality newsprint they’re destined to appear on, they’re purposely kept simple. These journalists are also working on a tight deadline. They need to transmit their work almost as soon as they’ve made it.

The second school is more nuanced, because the images they need to last longer. Newspaper images are designed to live in the moment and be discarded the next day, like the newspaper itself. Magazines come out only once a week, so instead of a daily deadline, their photographers are working with a weekly deadline.

This means, if a big event happens on Monday, the magazine won’t even hit the newsstands until the following Monday. Then that magazine sits on the newsstand until the Monday after that. Magazine publishers needed images with staying power.

The magazines are printed on slick paper stock, which demands higher technical standards. This is expensive, which means it’s for the advertising pages, not for our editorial content, but the better paper allows us to shoot higher quality film and in color too. Which is a burden as well as an opportunity.

To be clear, regardless of the school they’re working in, both groups are equally talented, and make exceptional images on a regular basis. The end needs of the mediums is what created the two schools of thought.

I’ll sum it up like this. If the first group comes back with mediocre images, it means the event was boring or uneventful. They are there to visually report what happened. If the second group comes back with mediocre images, it means they didn’t see it properly.

Now, the traditional photojournalists can be an arrogant bunch as well. Maybe it comes from always having the best seats in the house. But the arrogance of the second group, the “new photojournalists” is based in self-preservation. Imagine a big White House event like a peace treaty being signed. The traditionalists only have to make an accurate recording of the event. The new photojournalist needs to accurately record the event too, but they also have to interpret it with visual metaphors and symbolism that somehow gives their work a deeper, timeless, quality.

If you think you’re going to accomplish that, using the same gear and standing shoulder to shoulder next to several dozen great photojournalists… if you’re not arrogant, you’re already toast.

Maybe arrogant is too strong of a term. Perhaps, overly confident without any reason to be so, is a better way to say it.

Either way, it’s a fairly high bar to set for oneself, so naturally it became my raison d’être.

You see, the cameras around my neck had the potential to unlock the entire world for me. They were my all-access pass, which has a certain appeal. On top of that, if I used them right, they could even make the world a better place. Also appealing.

That’s some major overconfidence, bordering on the delusional, right there.

I realize this was my calling, but I also understood that nobody cared about my opinions or concerns. They didn’t care what I saw. They only cared about what I showed them. They weren’t interested in my feelings. They only cared about how my images made them feel.

The only thing that mattered is what I got on film.

The art of photojournalism is completely personal. It fails if it isn’t. But it’s not about you, as it fails if it is. This is the first of many contradictions that one needs to embrace.

Now, as dicey as my current situation was, wondering if I was going to blow up (in the wrong kind of way) in the next few seconds, there were a thousand other would-be’s who would have gladly jumped right into my shoes at that very moment.

And that’s how we all start out, self-absorbed, self-important, hungry, starving to make a name for ourselves. No different than any young professional working in any other business. Let’s hope I grow out of it.

The quality of the pictures and the motivation behind them is what self-justifies the act of intently witnessing the suffering of others.

When done right, pictures will change others. As highfalutin as it sounds, it does happen and more often than you think. Still images sway public opinion. They move those in power to act. They motivate average people to give, to become involved. Snowball enough of that together the hungry get fed, wars get shortened, or maybe never even begin in the first place.

This is serious stuff. As a photojournalist, your pictures will change somebody, even if that somebody is only you. Do them right, and they’ll change you for the better. Do them wrong and you’re not going to end up right.

So while one needs to acknowledge that there is a self-interest in play, they’d be foolish to embrace it too tightly.

Without the pictures, your cameras are worthless and you’re taking up space that can be better used by somebody else. Without your ego, you won’t have the courage to even step on the playing field. Without the proper intent, there’s no way you can make pictures that justify your presence.

There’s a delicate balance at play here. Any salvation you might receive won’t come through grace, it will have to be earned.

The distance between being just a gawker or hanging next to Goya is a short.

Right about now, is when the other two rocks exploded.

So it was a total of three, not four. Probably the first thing I’d gotten right today.

Over the years what I’ve learned about grenades, is when you hear them, and you haven’t been hit, they’re pretty much over. Which means they’re a lot less stressful than driving across a minefield or being targeted by snipers. Okay, maybe all aspects of warfare are stressful, but intense, fast stress is better than constant, nagging stress. Just my opinion, your mileage may vary.

If you’re not bleeding after the initial explosion of a grenade, there’s a chance to catch your breath and evaluate the situation. I used that moment to fight off the lizard brain and try and take back control of my own body. The more often one finds themselves doing this, the easier it becomes. Whether that’s a good thing or not is another question.

That said, a few weeks prior to this current situation, I’d been in Haiti working alongside one of the most celebrated conflict photographers of all time. We were in a wrong place/wrong time situation. Afterwards I asked him what he’d done when things turned awkward. He replied that he had ran towards the explosion.

Running towards the gunfight, long before an ad agency turned those words into a catchphrase, didn’t initially make a whole lot of sense to me. Luckily I was traveling a lot by air those days, before the personal entertainment systems became a thing, and had plenty of time to think it through.

After much pondering, I came away believing two things; One, that you should never get caught in the crowd, and two, the best way to do that was to run towards the trouble.

There you have it. Words to live by, or at least we hope.

If you’re a human, don’t be part of the herd, and if you’re a journalist, don’t be part of the pack.

That day in Haiti, just by luck, I wasn’t part of the crowd or the pack. If I was, I would have had no idea what was happening, I wouldn’t have been able to make any pictures and I probably would have been trampled (like a lot of other people). As it turned out, by not being in the crowd, I wasn’t able to make any pictures and I still had no idea what was happening, but at least I did not get trampled.

In this case, one out of three is not bad.

As a photojournalist, to not make meaningful pictures is to fail, which is what I did that day. Not breaking a limb is nice, but so is not losing your soul. That’s what you risk losing when you fail. Without the pictures you’re nothing more than a ghoulish tourist.

You’re photographing people at their most vulnerable in the midst of often horrible situations. You cannot be okay with failing them.

Heaven help your sorry ass if those half-made pictures win you an award or some other kind of personal recognition. Spiritually, you’d be better off cooking meth for a living.

You need to be there at one hundred percent, not coach speak either, but completely there. In a game where you run towards the explosions, without air support and armed only with a camera, you can’t do it halfway.

To do anything less is to cheat yourself, your viewers, and the people whose lives you are there to witness.

At the start of my career, I didn’t know what I was doing or how I was going to do it. My planning was poor, haphazard and careless, but I was at least fully invested in doing things right. There wasn’t a manual that spelled any of this out. This craft is taught by mentors and I had some great ones. So, although I didn’t know what I was doing, I did have a vague idea of the commitment that was expected of me.

Even if my pictures weren’t good, I still needed to do three things. Respect my subjects, respect my craft, and respect my audience.

Besides that, all one needs to do is work harder and smarter than they think they possibly can.

Simple rules, easy to understand, hard to follow. The goal is to do right by your viewers, yourself and the people you photograph. Doing this may not lead to fame or fortune, but it will help you to make lasting images.

And that is how I found myself, on an otherwise perfectly nice day in Belfast, sprinting through a cemetery towards an unknown horror and thinking that it all makes perfectly good sense.

If you have a moment, please take a look at The Curious Society. It is the physical manifestation of the thoughts and memories I’m sharing here.

Thank you,

Ken

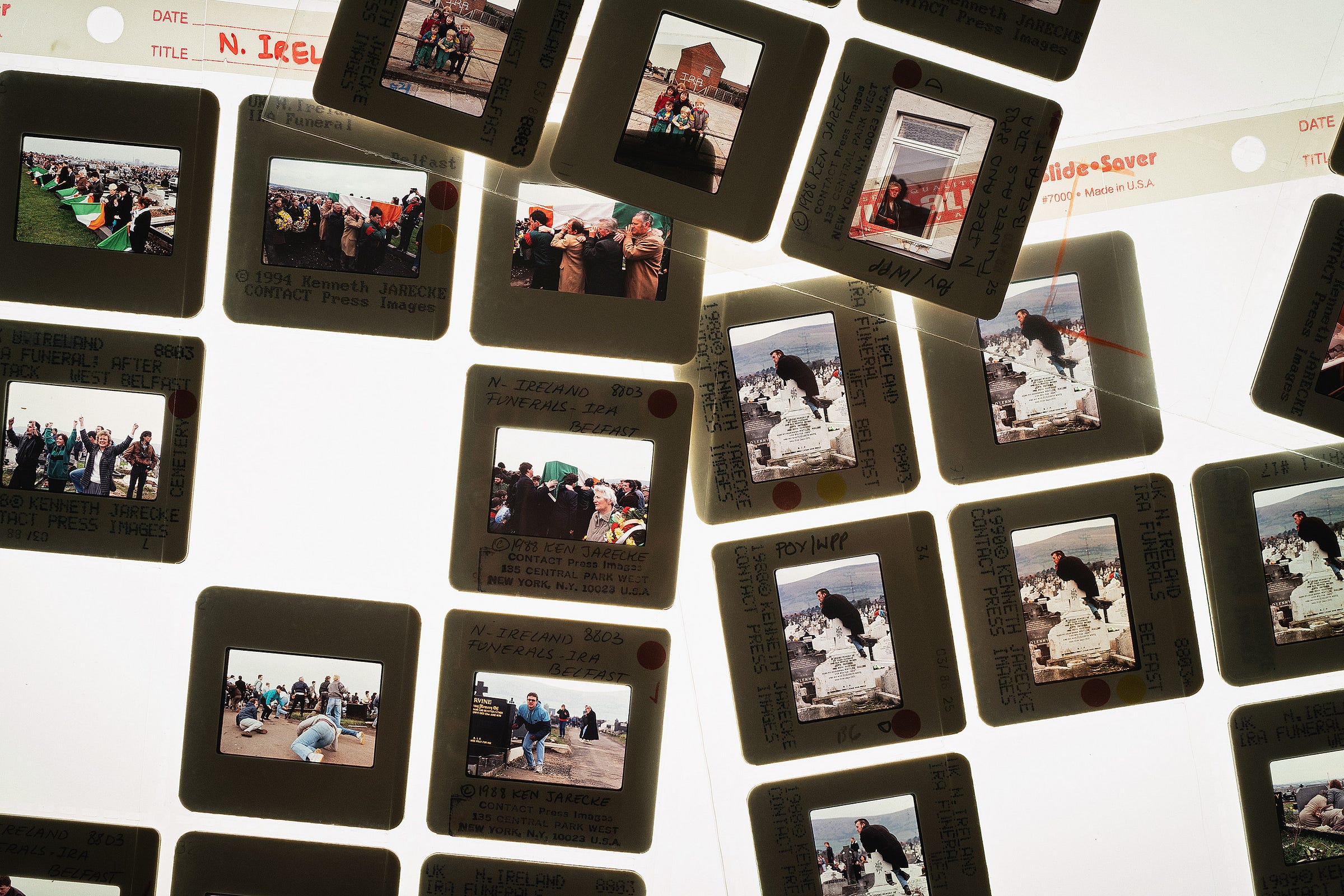

All text and images Copyright © 2022 Kenneth Jarecke